20 Books You Should Read This Summer

Here are 20 recently published or upcoming novels and non-fiction works to enliven time spent at the park, at the cottage—or on a comfy chair in the backyard.

Likeness by David Macfarlane

A gifted and admired writer across genres—his novel Summer Gone was nominated for the Giller prize, while The Danger Tree, a memoir of his mother’s Newfoundland family, brought him a chorus of praise—Macfarlane’s works have always focused on memory and family. That long-standing theme is understandably far more sorrowful in Likeness. Born out of the fatal illness of Macfarlane’s 29-year-old son, Blake, in 2018, it conveys grief in heartbreaking, often quietly stunning, prose. “When the worst that can happen, happens, the only useful lesson is the knowledge that it can,” he writes mid-book. “That’s the take-away: a world can actually end, time can actually run out.”

A gigantic John Hartman portrait of Macfarlane, with a background depicting an aerial view of his hometown of Hamilton, hangs in Macfarlane’s living room. Contemplating it, especially during Blake’s illness, brought Macfarlane, 68, a sense of his personal chain of being, of the essential likeness of grandfather, son and grandson. Thoughts of Macfarlane’s father, a taciturn doctor also named Blake, run from intense golf matches to drives through Hamilton when the older man would recount ancient gossip about the local elite. Newly vivid memories of his own youth and worries over Blake meant facing the painful contrast between the days of their youths, a time when the father felt limitless possibilities and the son lay in a sickbed.

The painting never leaves the story. The light it portrays and the light it reflects, the overall—aerial, in fact—view it provides of what was naturally no more and what may be cruelly cut short, evoke so much. Between asides that amuse and sadden equally—“And if I may, if your son or daughter asks if you want to grab a bite, say yes”—Macfarlane writes of the pleasure of walking with Blake when he’s in remission and of the days when “he was in such pain I thought my heart would break with helplessness. I would hold him, my 29-year-old son, sometimes for as long as half an hour.” There is an ache in Likeness that cuts as deeply as it does because of the beauty of its expression. - Brian Bethune

Probably Ruby by Lisa Bird-Wilson (Available Aug. 24)

A searing fictional portrait of intergenerational trauma, embodied by the unforgettable Ruby and her search for her Indigenous kin. Adopted as a baby, Ruby spent her lonely childhood being told she was specially chosen but never believing it. As an adult, she copes by drinking hard and falling in love often, all the while searching for her origins. This is a heartbreaking and revelatory work about the meaning of family, and the pain we pass through generations, as inescapable as blood: “Fury and love as big as the prairie sky, edgeless, boundless. What was ever inherited without grief?” - Michelle Cyca

Whereabouts by Jhumpa Lahiri

In one of the vignettes that comprise this novel, the narrator visits a friend’s vacant country home, in a valley with breathtaking views. Upon arrival, she builds a fire, makes herself a cup of coffee and goes for a walk. Reaching a creek, she checks her watch and turns back, cutting short a moment of tranquility. “Solitude demands a precise assessment of time, I’ve always understood this,” she recounts. While location provides the scaffolding of this novel—each short chapter is named for where it takes place, such as “At the Trattoria”—solitude is its raison d’être. As the single, childless, middle-aged protagonist moves between encounters with former lovers, old friends and strangers, she tells the story of a life lived alone, one that is steeped in both sadness and satisfaction. - Dafna Izenberg

Her Turn by Katherine Ashenburg (Available July 27)

How do you let go? For journalist Liz, who is 10 years past her ugly divorce, there are two paths in this novel. One is self-help books on forgiveness beneath a rich life filled with Italian classes, yoga and an ill-advised affair with her married boss. The other proves more tempting: her ex-husband’s second wife, Nicole, with whom he became involved during his marriage to Liz, has just submitted to the popular personal essay newspaper column “My Turn,” unaware that Liz is the editor. Against her better judgment, Liz begins a veiled correspondence with Nicole, knowing full well the situation is destined to explode. Liz embraces a chaotic, and compelling, path to catharsis and emotional liberation. - M.C.

Second Place by Rachel Cusk

The titular setting of Canadian-born British writer Rachel Cusk’s new novel is a rural cottage on the coast (in a country never named) that the book’s narrator—identified only as M—and her husband, Tony, built as a scenic retreat for artists. “We live simply and comfortably, and have a second place where people can stay,” M writes to L, an American painter whose work she viewed in a Paris gallery 15 years earlier. L prevaricates, but eventually he accepts M’s invitation. When he arrives with a beautiful and capricious young woman named Brett, M is dismayed. Is she in love with L, asks Brett one day. “No,” M answers. “I just want to know him.” In fact, M wants L to know her. She credits his work with unleashing an inner force that moved her to leave her first marriage and stake out a life of freedom and authenticity. Now, she wants L to see in her what she saw in his paintings. But L is cool toward M, sometimes even mean; he asks to paint portraits of Tony and the visiting Justine, M’s daughter, but spurns M, who is relegated to a different kind of “second place.” Cusk has dressed an incisive meditation on the meaning of art in a delicious psychodrama about three couples communing in the woods. - D.I.

Notes on Grief by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Anyone who has suffered loss in the past year or so has been forced to hold their grief in isolation, without the physical comfort that family and friends might otherwise offer. Adichie gives voice to this excruciating pain, writing about the death of her father and offering up her grief as a way to connect these lonely, disparate howls of loss. “Grief is a cruel kind of education,” she explains. “You learn how much grief is about language, the failure of language and the grasping for language.” - Amil Niazi

The Invention of Miracles by Katie Booth

A biography of Alexander Graham Bell—inventor of the telephone, co-founder of the world’s Bell Telephone Companies, sponsor of the first aircraft flight in Canada—that begins with the author’s grandmother dying in hospital while being denied access to a sign-language interpreter is not going to unfold like any other Bell biography. The great inventor had a deaf mother, a deaf wife and a lifelong commitment to helping deaf people that both sparked and dwarfed his interest in his voice transmission machine—and incited a rage in the deaf community that has yet to subside. Booth, who grew up in a mixed deaf-hearing family, writes passionately—in a compelling mix of anger and sympathy—about a brilliant but blind obsessive who never even thought of asking the deaf what they wanted.

And that was the vibrant culture Booth describes, which, like that of any distinct collective, is expressed through its own language, ASL, the American Sign Language that had flourished for decades before Bell. But Bell saw deafness as something to be culturally eradicated, through merging the deaf into wider society by teaching children lip-reading and speech, and by suppressing sign language. His influence was a potent force for that trend in deaf education, and thousands of children—including Booth’s older relatives, to their sorrow—attended schools for the deaf that forbid signing. Miracles is a marvellous look at one man’s complex legacy. - B.B.

While Justice Sleeps by Stacey Abrams

This legal thriller by Abrams sees an ambitious law clerk take on a dystopian challenge to civil liberties and democracy. As law clerk Avery Keene becomes the linchpin in a complex and controversial case, she gets caught in a power struggle that could cost her her life. Despite the book’s slow start, Abrams is a strong novelist whose deep understanding of both politics and the law come together to form a page-turner about an intriguing legal and medical battle. It’s a wonder the former gubernatorial candidate and political organizer found time to write it while playing a pivotal role in turning the historically red state of Georgia blue to secure a Joe Biden presidency. - A.N.

Hummingbird Salamander by Jeff VanderMeer

Every VanderMeer novel is not just about how we have wounded the natural world, but also how we fail to see the damage and how we must change—through violent social and economic disruption—before we can see it. As one Hummingbird character who wants to bring on the disruption now—when there is still something natural left to restore—puts it, humanity’s ability to ignore the damage done is our species’ “fatal adaptation.” The transforming power of disaster was the theme of the author’s bestselling Southern Reach trilogy (Annihilation, Authority and Acceptance), inspired by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill of 2010. That underlying message is even more urgent here, in a novel that is part dark thriller, part angry condemnation of wildlife trafficking, part sci-fi fantasy, and wholly riveting.

It’s narrated by “Jane Smith,” a six-foot-tall former college wrestling champ turned middle-aged security professional with an aversion to naming names. After a café barista hands her a key and a storage unit address, Jane finds a stuffed hummingbird and an enigmatic three-word note that reads, “hummingbird .. .. .. salamander, Silvina.” The signatory turns out to be the estranged daughter of a billionaire sociopath (whose businesses include wildlife trafficking), an eco-terrorist (who bombed wildlife traffickers), the creator of a revolutionary biotechnology that might save the planet—and, by this point, already the victim of a fatal hit and run. Why Silvina chose Jane—the two women had never met—to complete her work is a puzzle that’s answered in one of the novel’s dizzying plot twists. But why Jane accepts is a matter for readers to unpack themselves.

Jane has a horrific childhood backstory that goes a long way to explain the lies and secrecy that permeated her adult life, even before she sets out on Silvina’s path. VanderMeer presents Jane as the entire human species writ small: she is not consciously aware of the price she paid for the abuse experienced in the past; she averts her eyes from the damage she is currently wreaking on her husband, her daughter and her work colleagues, who all suffer the blowback—from impoverishment to beatings to death—she puts into motion. She compartmentalizes, rationalizes and dodges, right up until the mess she makes is too overwhelming to be ignored. Jane, in truth, is profoundly unlikable and deeply sympathetic at the same time, a symbolic character to love or hate in a brilliant novel. - B.B.

Sufferance by Thomas King

This rambling, satirical gem of a story is told by a curious narrator. That’s “curious,” a favourite King word, in every sense. Jeremiah Camp, known as the Forecaster in his former professional life, is a genius at pattern recognition, partly because of his desire to know what is coming over the horizon. He’s also one peculiar character: having had a good look into an abysmal future (personal and societal), Camp has tumbled into existential despair. He quits his job, ditches his phone, TV and internet access, and moves to an isolated locale, where a small settler community abuts an even smaller First Nations reserve, once home to his mother. The solitude Camp craves, however, is not to be. Neither the locals—who provide most of the humour—nor his former associates will let him be. A billionaire wants to know the meaning of a list of 12 billionaires once drawn up by Camp, now that they have begun dying at a statistically implausible rate.

It’s all hard for the Forecaster to cope with, given that he is determined to stand by his vow of silence. It’s no easy task to craft a novel in which the protagonist won’t answer the barrage of questions aimed at him, but King carries it off brilliantly. Camp thinks answers that readers are privy to while forcing other characters to work out the responses themselves. And other, more rhetorical questions—Why did this bad thing happen? Do you really belong here?—simply hang in the air, made powerful by the echoing silence. Small wonder King has talked about the many false steps he made over years in trying to get Sufferance into shape, the thoughts he has also expressed about his non-fiction work, The Inconvenient Indian—the two books that are arguably his finest. - B.B.

Find You First by Linwood Barclay

One of the most internationally popular Canadian writers at work today, Barclay is a celebrated master of his patch of the domestic noir world, featuring a long line of suburban Everymen tumbling down some dangerous rabbit holes. That’s an overgeneralization, to be sure. Miles Cookson, the protagonist of Barclay’s newest thriller—who commutes by Porsche from his secluded $11-million home—is not remotely suburban. But the tech entrepreneur does fit tightly into a deeper Barclay theme: Miles has family issues, to put it mildly, and good reason to worry about them.

The novel opens with a kind of prologue, when two professional killers with an exceptionally meticulous cleanup routine—think bleach and fire—dispatch a 21-year-old scam artist named Todd. A meeting in a doctor’s office that occurred three weeks earlier then kicks off the main storyline. A shattering diagnosis—Cookson, 42, has Huntington’s, a relentlessly progressive, hereditary and fatal brain disorder—gets the solitary billionaire thinking about his only known family, a brother he loves and a sister-in-law he despises, and about his potential unknown family.

Two decades earlier, still working on what would become money-spinning apps and desperate for cash, Cookson had contributed to a sperm bank. How many potential heirs—of his billions and his genes, offspring who might well eventually need expensive medical care—are out there? A little judicious bribery later, and Cookson has a list of nine. Todd is one of them; soon others on it also begin to fall off the map, not simply disappearing but bleached out of the DNA record. Cookson and an aspiring filmmaker named Chloe, the first of his listed children he approaches and the only one who had actively been seeking her father, negotiate an uneasy trust as they try to understand what is happening and why.

Throughout, Barclay’s superb sense of pace, the sine qua non of thriller writing, is on full display. There are plot twists galore, coincidences that don’t make readers roll their eyes, nicely etched characters (even the minor ones), and a spectacular crash ending. In short, Find You First is great entertainment. It’s also a thorough meditation on family bonds, obligations and betrayal on all sides, involving just about everyone in it, and a fine novel. - B.B.

World travel by Anthony Bourdain and Laurie Woolever

Before his death in 2018, Bourdain had a meeting with Woolever, his long-time assistant and collaborator, to plan “an atlas of the world as seen through his eyes.” The resulting guidebook collects Bourdain’s ideas and opinions from TV appearances, interviews and writing. This isn’t a travel book you schlep with you; it’s more a sourcebook for daydreams, to imagine a life of travel in the post-pandemic future, or a world in which Bourdain’s distinctive voice still exists to tell stories about a place. - Naoko Asano

New Yorkers by Craig Taylor

Following the success of Londoners, Taylor’s oral history of London, the author moved to New York with a mission: to listen. He spent six years interviewing New Yorkers; the 75 of them featured here include an elevator repairman, a bodega worker, the mother of a Rikers inmate, and a “lice consultant.” Reading their stories—which together build a portrait of the city in all its contradictions—feels like eavesdropping on conversations in the best way. - N.A.

Everyone Knows Your Mother is a Witch by Rivka Galchen

Set in an era increasingly resonant with our own—pestilence, rampant conspiracy theories and huge scientific advances were all hallmarks of the early 17th century, too—Galchen’s novel is based on a striking historical curiosity. In 1618, Katharina Kepler, mother of Johannes Kepler, discoverer of the laws of planetary motion, went on trial for witchcraft. Little is known about the real-life Katharina, but her fictional counterpart—elderly, illiterate, stubborn and as intelligent as her iconic genius of a son—sparkles in this prickly and often black-humoured story. - B.B.

Doom by Niall Ferguson

As we’ve become acutely aware over the past 15 months, humanity has been inextricably linked to and shaped by disease. Pandemics have shaped our culture, politics and economics, forcing us to twist, turn and adapt in reaction to both the devastation and innovation they have wrought.

The problem, as Scottish historian Niall Ferguson lays out in his new book, subtitled The Politics of Catastrophe, is that regardless of this long history, we seem determined not to learn from our mistakes, seemingly doomed to repeat our missteps in perpetuity.

Like many epidemiologists and historians before him, Ferguson understands that COVID-19 will not be the last disaster we face in our lifetime, and so in Doom he probes the various factors at play to help us better understand how we respond in the face of crisis and why. Ferguson makes clear the reasons catastrophes don’t exist in isolation and why it’s so important to look beyond each one to its inciting factors. “Even a catastrophic earthquake is only as catastrophic as the extent of urbanization along the fault line—or the shoreline, if it triggers a tsunami,” he writes. “We cannot understand the scale of the contagion by studying only the virus itself, because the virus will infect only as many people as social networks allow it to.”

Despite its gloomy, foreboding title, Ferguson’s book actually provides comfort to anyone seeking context and meaning in how this pandemic has played out, as it deftly lays out the historical imprint of catastrophe on human life. In doing so, he relieves us of the anxiety that we are navigating the future completely in the dark. - A.N.

What Strange Paradise by Omar El Akka (Available July 20)

Another rickety ship overloaded with migrants flounders off a Mediterranean island, and only nine-year-old Amir comes ashore alive. Panicking, he flees would-be rescuers and is hidden by Vanna, a local 15-year-old with her own reasons to be alienated from fellow islanders. El Akkad’s novel, which unfolds in chapters alternating between Amir’s life before and after the disaster at sea, is far more muted than his stunning 2017 debut, American War. But that low-key approach actually adds to Paradise’s slow-building power. It also alternates between a familiar tale—two children on a perilous quest for safety—and a larger crisis, less familiar only because we choose to ignore it.

After years of refugees washing ashore, alive or dead, the islanders, inured to the shock, mostly worry about the tourist trade. The tourists, who come to the island to leave their—and the world’s—troubles behind, are even more deliberate in their gaze-averting, paying attention just long enough to cheer when the authorities announce a beach has reopened. The novel’s true theme, the awareness that runs inches below the surface throughout, becomes overt in El Akkad’s final, searing paragraph: Amir and Vanna are up against the world’s indifference, not its hostility. - B.B.

Driven by Marcello Di Cintio

There are few spaces as consistently intimate and yet ultimately anonymous as that of a cab. In his new book, subtitled The Secret Lives of Taxi Drivers, Calgary-based Di Cintio writes, “As passengers, we rarely wonder at the lives of those we know only by the reflection of their eyes in a rear-view mirror.” He presents a varied, eclectic collection of stories from the frontlines of North America’s taxi industry, showcasing the indomitable hope of the people who literally keep our cities moving forward. - A.N.

Seed to Dust by Marc Hamer

This account of a year in the life of the garden Hamer tends in Wales is, naturally, as much about the gardener as the life in his care. Hamer moves seamlessly between the natural world—there’s an entire chapter on aphids—memories of his hardscrabble younger years and expressions of class resentment directed at his long-time employer, the kindly but aloof garden owner he calls Miss Cashmere. There are as many echoes of English literature, from Dickens’ Miss Havisham to—in a highly platonic way—Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley and Mellors, as there is entrancing natural lore in this distinctive memoir. - B.B.

The Bomber Mafia by Malcolm Gladwell

How do humans come to believe that the possible is also permissible? That’s the dominant theme in this absorbing dive into what military leaders thought, in the years before and during the Second World War, would be the conflict-shaping effects of air power. How would it be used against their side, and how should they use it against the enemy?

The British foresaw terror on the home front, predicting millions of casualties and psychiatric hospitals filled with traumatized survivors, and resolved to bring the same to Germany. Watching the Luftwaffe rain bombs on London, RAF Marshal Arthur “Bomber” Harris—a man Gladwell calls a psychopath—remarked that the Nazis had sowed the wind and must thereby “reap the whirlwind.” For their part, the Americans dreamed of surgical strikes, Gladwell writes, precision factory-bombing that would cripple an enemy’s capacity to wage war, ending conflict at minimal human cost. And just as the British carried on their aerial assault despite knowing the Blitz had not fractured their own morale, the Americans ignored their inability to target precisely, and kept their faith in surgical strikes. Until, that is, the war in Europe began to wind down.

In the Pacific war everything was different, from the stakes (invading Japan was projected to cost a million Allied casualties) to ever more lethal weapons (napalm) to a new key personality: bomber-in-chief Gen. Curtis LeMay, whom Gladwell notably does not call a psychopath, although he writes that LeMay was “incapable of self-doubt.” LeMay was also convinced—and convincing—that the most humane way to wage war was to end it quickly, even if that involved mass civilian deaths. The switch flipped from precision to carpet bombing. On March 9, 1945, U.S. planes firebombed Tokyo, immolating 100,000 Japanese, more than the atomic blast would later kill in Hiroshima. (LeMay, who went on to firebomb another 66 cities before Japan surrendered, always believed atomic bombs were superfluous.) Gladwell’s beautifully written account will surely be seen as simplistic by historians, but it is sharp-edged in its moral urgency, a book-length introduction to a brief question: what would you have done? - B.B.

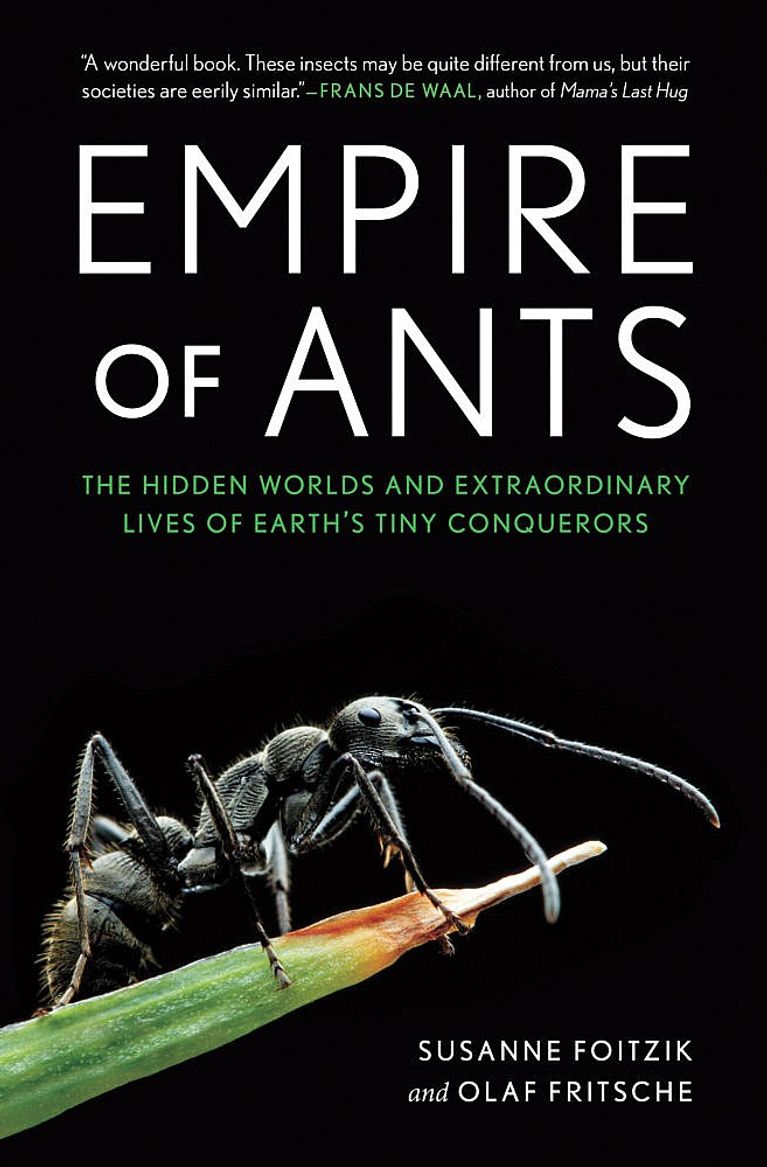

Empire of Ants by Susanne Foitzik and Olaf Fritsche

All insect experts, even those who study parasitic wasps, admire their subjects, but myrmecologists have always leaned into an enthusiasm that borders on adoration for their guys, the 10 quadrillion ants of planet Earth. It’s not the numbers, of course, that spark their interest, as Foitzik, an eminent German evolutionary biologist, and her biophysicist co-author, Fritsche, explain in their informative and entertaining tribute. Far more enticing is the extreme variety that 100 million years of evolution has wrought among ants.

The 16,000 known species exhibit a size differential that matches mice and men—a pharaoh ant can walk about on the head of a carpenter ant. Colony populations exhibit the same spread, from a few dozen inhabitants tucked neatly into an acorn to three million or more leafcutter ants in a single mansion-sized structure of a thousand rooms, complete with ventilation systems and waste-disposal facilities. Evolutionary strategies are as varied: some hunt termites, marching army ants indiscriminately consume every creature in their path, and leafcutters, whose colonies are the largest and most complex non-human societies in the world, bring vegetation back to the nest to provide for the fungus they domesticated 15 million years ago.

And then there are the behaviours that simply boggle the authors, who gathered them into a chapter called “Crazy Critters.” High on the list is a Malaysian ant in possession of a large gland full of sticky, foul-smelling, corrosive, toxic goo and a readiness to use it. When threatened, it will tense its muscles so powerfully that its abdomen will split apart “like a water balloon,” thereby ripping apart the poison gland and spraying its contents on attackers. Coated in toxins, enemy ants will die alongside the suicide bomber, while larger predators will recoil from the stench and the futility of the hunt. The latter group, Foitzik and Fritsche cheerfully add, includes myrmecologists, “driven mad [because] are particularly prone to exploding when you’re trying to collect them with tweezers.”

In the end, though, the true allure of ants lies in something the authors revisit time and again—the way the insects are both profoundly alien and very like us. On the bad side, loosely defined, various ant species practise slavery, conquest, mass destruction and unsustainable resource extraction to a degree barely known outside human activity, while on the good, altruistic ant behaviour is off the charts. Those eerie, uneasy echoes mean ants will always fascinate humans. - B.B.

GET CHATELAINE IN YOUR INBOX!

Subscribe to our newsletters for our very best stories, recipes, style and shopping tips, horoscopes and special offers.